Critical Texts

Catalogs 1979/2018

Both in the images that address the world outside and those that depict interiors- or, in the artist’s own words, the inner world-light plays the leading role in the paintings of Marcos Duprat and he captures it through the rigorous and traditional technique of velatura. This is the making of color through the building up of transparencies and the superposition of several layers of oil pigment. As the great critic José Guilherme Merquior has remarked on the occasion of one of Duprat’s exhibition “ It is a slow painting, adagio-like, favouring meditations on the double, the well pondered series, the research into depth.”

So the paintings of Duprat, as any true work of art, are produced through a dialectic -of love and struggle -between his initial intentions and the attention to the demands, whims and suggestions of the work in fieri.

At each step, he is called by the painting itself to develop new pictorial solutions, determined by the needs of each unforeseen situation as well as by new opportunities. Duprat has a deep knowledge of the complex relationship between the painter and the working materials as well as the technique he uses. It is undoubtedly through his subtle and wise use of velatura that he achieves the extraordinary chromatic vibration of his works.

In the paintings that relate to the interior world it is prevalent the use of windows , doors , corridors and passages and , on another level, mirrors that, through their own reflecting faculty, evoke the possibility of introspection, or, in other words, an even deeper interiority. In fact, it should be noticed that the suggestion of self contemplation extends itself to the images that depict the outside world – the luminous reflections in the liquid surface of seas and lakes- and point out to a return to the inside world . So we have an on-going speculation movement between inside and outside, and vice-versa. The painting of Marcos Duprat ( opening a parenthesis on the merely instrumental and utilitarian perception of the world so domineering in our daily life) invites our imagination not only to look at the pictorial surface but furthermore to explore and dive into these transparent corridors, mirrors, passages, lakes and seas.

Antonio Cicero Lima

Rio de Janeiro, 2018

Marcos Duprat is one of the few artists of his generation with a cultivated, formal, academic grounding. He alternates between painting and drawing as he incorporates into his images memories and life experiences. The exhibition Memories on paper celebrates four decades of his work in drawings, pastels and watercolors. Marcos Duprat experiments with new materials and textures. He reconstructs space with particular craftsmanship offering the viewer a composition full of elements, with a light of their own, inviting us to dive into the pictorial space. Each work has its own identity, its choice and, above all, its lyrical poignancy.

We thank all those who made this exhibition possible. Marcos Duprat has created a body of work that is rigorously developed and imbued with a deep humanistic feeling.

Welcome to the Memories on paper exhibition!

Monica F. Braunschweiger Xexéo

Director of MNBA / IBRAM / MinC, 2017

Marcos Duprat is a Brazilian artist whose work is relatively unknown in his own country.

The exhibition LIMITES/BOUNDARIES assembles a selection of sixty works of his private collection spanning four decades of creative activity intertwined with his diplomatic career. These paintings – oils on canvas and on paper, pastels, watercolors and pencil drawings – trace his evolution from figurative to abstract art.

As a whole, Marcos Duprat’s work has its roots in his singular and fruitful life experience as both an artist and a diplomat, with an attentive look to the most significant developments in the domestic and international art world with which he has had a direct and enriching contact. After pursuing his Masters in Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., seven years in Europe and nine in Asia have left a clear imprint in his work.

Following the examples of Bill Viola and Hiroshi Sugimoto, contemporary artists that act as curators of their own presentations, Duprat is the curator of this exhibition.

The National Library is pleased to host and share with the public in Rio his artistic path.

Helena Severo

President of the National Library, 2016

Passages

This exhibition sees the awaited return of Marcos Duprat to São Paulo after a fiver-year absence.

It is the showcase for a wide-ranging selection, encompassing his early production all the way through to recent pieces, and is intended to illustrate the developmental process of the growth and transformation his work as a visual artist has undergone.

As an autonomous and independent creator, the artist is also the ideal curator of his exhibitions.

As the chooses and offers to the public view the works that he feels as crucial and determining to the development of the ensemble of his work, he also opens to the viewer the possibility of participating in his own and intimate sphere of creativity.

Duprat’s artistic background started at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro and progressed through his interest in painting and, in the 70s, the pursuit of his degree as Master in fine Arts at American University, in Washington, D.C.

His earlier work, fresh and imbued with a touch of youthful sensuality, show the influence of a new figuration prevalent at the time in the United States. However, these works diverge form the photorealism of the time as, even the, he softens the edges, creating a flow between the figure and the surrounding space, employing soft and free strokes.

His use of a delicate color scheme is an expression of his goal of perceiving light as the center and essence of the canvas.

Due to his demanding professional activities, his work during this period was done in the studio, often a night, under artificial lighting, or with the windows wide-open on the weekends. Duprat explores the boundaries of the studio. The colors are mostly cool.

Human figures, when they appear, are surrounded by walls and doors. Windows and corridors are witnesses of the creative introspection of both the models and the artist. There is a psychological distance between the artist and the figure, a withdrawal that imbues it with an evocative, almost abstract, quality. In these stark interiors, windows and mirrors play a game of transparencies that suggest narcissistic dreams and the investigation of the double and its deep emotional resonance.

The works produced while living in Lima, Brasilia, Milan, Montevideo and Budapest show a color scheme that remains largely unchanged, although the chromatic treatment is rich and full of nuances.

At the turn of the century, Duprat returns to Japan, where he had previously lived in his youth and from where he had retained his affinity with Japanese aesthetics. From now on there is a liberation and an enrichment of his palette. There is a renewed boldness in his execution as nature becomes a source of interest to his sensitive drawing.

Light continues to be a tool in the creation of the image, now leading to dreamlike landscapes and the contemplation of spaces virtually structured by color.

The exhibition assembles around fifty works on canvas and paper. Duprat uses the velatura technique, in which colors result from the superposition of several layers of pigment.

He uses oils on canvas, and oils, pastels, watercolors and pencil in the works on paper.

American critic Ben L. Summerford remarks that, in his paintings there is, “… a quality which acquires substance in a timeless space of shining light, reflecting not events in themselves, but knowledge of potentialities…”

The recent and ongoing work reveals substantial renovation.

The pictorial surface is composed of color fields that expand as they are built with a brushwork that follows a radial or concentric rhythm. The tension generated suggests the effect of the refraction of light in the atmosphere and creates surfaces that evoke or describe color horizons and landscapes.

Vera Pedrosa

Rio de Janeiro, 2015

MYSTERIOUS BEAUTY OF SPACE WOVEN BY LIGHT

According to Genesis, light is in the very source of Creation. In the Paleolithic age, man painted for the first time, as in the cave of Lascauxu, under the beaming light of fire. In this flickering light, animals would hop around the cave walls, and maybe that was the very first museum in human history.

Light is also one of the fundamental sources of painting. The Madonnas of Raphael, Da Vinci’s smile of the Gioconda, the portraits of Rembrandt, all these artists have endeavored to capture the mystery of light and shadow. This subject matter still prevails through the passage of time, even now, when one witnesses dramatic changes in the artistic forms of expression.

Marcos Duprat, born in Rio de Janeiro, has developed his significant career as an artist. making the core of his expression the aesthetics of images woven by nature’s gift: light. His main themes are figures, interiors, and still-lifes, which are subtly connected with each other. Water and mirrors – which appear frequently in his paintings obviously symbolize an attraction to introspection, fantasy, and aesthetic narcissism. The quiet interiors of Vermeer, Bonnard’s exuberance in his depiction of light and the somewhat haunting atmosphere characteristic of Hopper – by absorbing influences

from these artists whom he admires, Duprat explores endlessly his own transparent corridors of light. It has been four years since he came to Japan, and one anticipates in his upcoming one-man show that he has further expanded his sphere of expression by his encounter with oriental space.

Miki Kaneko

Fujyia Gallery – Tokyo, 2004

“It is hard to define the specific place of easel painting nowadays. One of the reasons for that is the current recession- in the art production market as well as in its criticism – which followed the boom of the eighties. Undoubtedly, first class artists have emerged from that period. However, it could be said that this critical acclaim and euphoria of commercial success has had a negative impact on the historical legacy of the medium of painting. The painting of Marcos Duprat, however, is free from this troublesome context. It defines its own way laboriously owing nothing to the opportunism of both fashion and the art market.

Also, it does not address the conceptual questions or the definition and role of art. The influences that come from the past – especially those of Italian post-impressionism – are not related to the academic connotations of post-modern classicism. Those influences are, in fact, used fully, as authentic tools for an intensive personal search. The critics are right to point out light as the leading element of this plastic universe. I would add that light is the very substance of Duprat’s pictorial space. All the magic of these paintings is the possibility of entering illusory spaces which unfold beyond the surface of the canvas. In his series of works “Passages”, the mystery of space is free from any prosaic detail. It is not the homogeneous and centralized space of classic painting, but, as the title suggests, the experience of a passage to a region of indefinite borders. One space leads to the other, and then that one to another … The open doors show as much as they hide. They almost stand as a symbol of vision, or of desire, always oblique and fragmented … “

Valéria Gonzales

Fujyia Gallery – Tokyo, 2004

Day Dream

Marcos Duprat is a gifted man. He has one visage as artist and another as a diplomat.

Regardless of the fact that neither of these are easy tasks, I would say he is an exceptional example of having pursued simultaneously and yet steadily two different lives. The secret of his development as a professional artist as well as a diplomat is that he managed to bridge two fundamentally· different worlds: civilization and culture.

The pursuit of rationalization and evolution in a civilized society organized in different nations and the expression of emotion and individuality through art do not in any way appose or conflict with each other. On the contrary, it is possible that these two activities interact with each other to produce a substantial multiplied effect. A diplomat ‘s work is to bring together people and countries in good will. Art is not general knowledge or the ability to promote good relations.

Art is an intellectual and deliberate act of self-expression as well as a perception of one’s own life and thoughts which takes material shape. More than the usual skills of a diplomat – related to civilization – Duprat, deeply involved in his inner search as an artist, has the keen knowledge and technique of expression which ·give him access to another world, that of culture.

Let us now look at the works of Marcos Duprat. The underlying theme that permeates his work is light, time and space. This is an eternal and universal theme for an artist.

This is distinctly expressed in the series of paintings on the four seasons shown in this exhibition.

Living in Tokyo for two and a half years, the artist has been stimulated by the gentle light and the change of seasons in Japan. He frequently goes out sketching nature around the area of Shiroganedai where he lives. Duprat has a natural preference for glowing colors and fills the canvas with light almost to the point of its saturation, which may, at a first glance, lead to impressionism. However, when one observes carefully, in spite of the intense play of light and shadow, the material existence of the painting is ethereal, with an almost atmospheric qualify, and the harmonious co/or scheme is evenly orchestrated. The artist has referred to Bonnard and Morandi among his main sources of inspiration. Indeed the technique of “valuer” – or “velatura”, the superposition of several layers of paint – the use of light and shadow and the composition show the influence of these painters.

The world created by this artist is all an illusion of a subtle reality extended beyond a transparent film. Or is. it more appropriate to call it a day dream? The artist has worked extensively with photography along his career. The work of cutting off and clipping images into frames is perceived also in his oil paintings. That can be seen as much in the still lives, influenced by Morandi, painted in divided frames, as well as

in the trees in the garden, seen through the window frames. Photographs are also called pictures of light whose contents of expression vary with the strength of its radiance. The surface of the water or the shapes of fish in water drawn by the artist are as though light has penetrated the lens. as if light itself has been permanently set on the canvas.

Marcos Duprat also shows interest in architectural spaces. He has produced a considerable number of interior scenes characterized by vertical lines, which accentuate the feeling of passages, spaces that extend from the foreground to the very depth. In spite of the geometric composition, there is nothing executed with rigidity and the lines are drawn with a free hand. Considering the artist is essentially a colorist the paintings might tend to be intensely and heavily colored but in this case. they are strangely and mysteriously luminous.

That happens because of the light, which comes in through open doors and windows, as well as the expanding outside space. where the breeze blows. The artist has mentioned that, since his arrival in Japan, he has been attracted to horizontal compositions, which developed as he became progressively involved with Japanese natural features. This may be related to the concept of Japanese nature and gardens. The works exhibited’ this time reveal contrasting concepts such as nature and artificiality, straight lines and curves, light and shadow, East and West. the unseen presence of someone and a sense of solitude, which comprise the charm of his work.

Artists. in fact – more than “professionals”, as mentioned previously – may be people with a fine sensitivity and a longing for solitude.

Takeshi Kanazawa

PromoArt Gallery – Tokyo, 2003

Acompanho o desenvolvimento da obra de Marcos Duprat. Desenho e pintura são os meios de expressão plástica dos quais o artista se serve, sempre pautado pela observação e apurando a qualidade das técnicas que usa. A fotografia exerce também um papel significativo em sua obra, não propriamente como referência direta para o desenho, mas como registro de memória, depois trabalhado e filtrado pela emoção do artista.

Os interiores são o seu enfoque preferido. Ele monta cenas da vida cotidiana com apetrechos diversos e com personagens, vez ou outra, apenas insinuados por metonímias. Cada elenco de obras representa parte de um discurso plástico que se sedimenta a partir da leitura de todos os quadros da exposição que configuram um sentido e um rumo explícito.

A mostra atual aborda a importância significativa da luz na representação plástica. E ela se diz presente e

transformadora das cenas dos quadros através dos espelhos, reflexos, transparências e da sua imagem incorpórea. Cada um desses agentes intervenientes tem força ilimitada e sofrem a interdependência da visão do espectador.

Em primeira instância, as cenas, ou seja, as pinturas, compõem-se de formas, volumes e cores que estruturam o espaço das composições plásticas. Num -segundo momento, a luz transformadora, criada pelo artista, ocupa o espaço da tela com grande energia, levando-nos a avaliar quão voluntariosa e invasora ela é ao penetrar na área pictórica. Certo que ela ocupa as cenas com o propósito incomum de desarticular e desconstruir a composição já existente. Trava-se um jogo ótico entre o corpóreo das cenas e o incorpóreo da luz. E assim, o artista esborrifa grãos de luminosidade sobre os volumes, cadeiras, mesas, portas e janelas, criando uma interação entre o visível e corpóreo e o devir a ser do visível e incorpóreo da luminosidade, aderente, fugaz, ao mobiliário represado nos interiores.

Como personagem central da pintura, a luz insinua ao visitante uma relação amorosa e condicionante às coisas. E, por que não aos homens? E aqui cristaliza-se o mistério exposto na instalação Limites que, para ser realizada, requer a presença do espectador debruçado sobre seu espelho de vidro, observando a simulação de água e as pedras que jazem no seu interior. Para existir e ser apreciada, a obra exige luz. E interdependente dela, incorpórea e agora não dependente da mão do artista. Apesar de corpórea, a instalação, para ser vista e fazer-se espelho, precisa da claridade natural ou da elétrica.

Desvenda-se o mistério. O espectador vê a sua imagem refletida na superfície de vidro. Questiona-se. Seria ele uma obra de arte? Questiona-se da mesma forma que Marcos Duprat, ainda menino, saindo do colégio e aguardando o ônibus sob a chuva, viu, de repente, a calçada cheia de buracos e uma poça d’água reproduzindo o céu azul e a luz do sol dourando tudo. A água é também espelho da criação.

A compulsão de trabalhar os mistérios da luz acompanha a trajetória artística de Marcos Duprat. São quarenta anos de desenho e pintura. Muitos dedicados à relação com a luz, no seu mais amplo espectro. Trabalhou com modelos-vivos, refletidos nos espelhos, o céu, o mar, a natureza morta e a figura. Remetia-se àquilo que se diz realidade aparente, preferindo-, contudo, dar asas à própria imaginação. Desenvolveu-se nas técnicas da pintura e do desenho, capacitando-se na engenharia dos estilos que

compõem as suas cenas pictóricas. Conviveu com as tendências artísticas da pop art, arte conceituai, land art e de outras tantas artes, preferindo seguir seu caminho de pesquisador das cores e da luz, buscando reencontrar o fio da meada do seu encantamento de menino – a imagem do céu azul e do sol refletidos na poça d1água -.

Rahda Abramo

CCBB – São Paulo, 1999

MARCOS DUPRAT UN MAESTRO DE FIN DE MILENIO

Marcos Duprat (Rio de Janeiro, 1944), es un notable artista plástico brasileño, desconocido en Uruguay, pese al vínculo estrecho que nos une al vecino país, a través de la Bienal de San Pablo, creada en 1951, y desde hace dos años de la 1ª. Bienal de Arte del MERCOSUR en Porto Alegre.

Su lenguaje está muy distante de los grandes creadores que se sucedieron en su país natal a lo largo del S.XX: Portinari, Antonio Henrique Amaral y el “Tropicalismo”, Marcelo Grassman, etc. y todas las vanguardias que les siguieron e irrumpieron no sólo en Brasil sino en toda Latinoamérica y en nuestro país sobre todo a partir de las prédicas del maestro Joaquín Torres García, y posteriormente de los geométricos José Pedro Costigliolo y María Freire.

Duprat es actualmente Cónsul General y Ministro de Brasil en Uruguay. Su condición de Diplomático lo llevó por distintas regiones del mundo. En 1966 le toca como destino Japón y allí realiza un Curso de Dibujo con el tema de la figura humana en la Universidad de Waseda, Tokyo.

Entre 1974-77 cursa una Maestría en Bellas Artes en The American University, Washington, D.C.-EE.UU. Tal pasaje por los diferentes continentes y culturas le posibilitó estudiar el rute universal, lo que contribuyó a la elaboración de un lenguaje muy personal.

Sorprende el arte de M. Duprat en un mundo inundado de “Instalaciones”, de “Arte Conceptual”, de “Arte por computadora”, de “Intervenciones” y “Happenings” con sus enormes telas pintadas al óleo que tienen como tema central la figura humana y la luz.

El primer deslumbramiento al enfrentarnos a sus cuadros resulta de esta última que inunda la mírada del contemplador y lo sobrecoge.

Uno de sus motivos centrales lo constituye el desnudo tratado con absoluto ascetismo, enfrentado a espejos, puertas siempre abiertas, ventanas y escaleras por las que irrumpe la luz, símbolo de esperanza, de apertura y paz.

Se reiteran en otras series los temas del agua, la tierra, el cielo y el aire. Los muros son siempre metálicos o vidriados en los que se refleja la imagen del hombre, asexuada, apenas una leve curva denuncia un cuerpo femenino, pero de una enorme euritmia, en actitud de autocontemplación.

Pese al aislamiento que denuncian sus estilizados cuerpos, revelan esperanza en la actitud distendida y expectante, siempre enfrentando la luz, sin angustia, serenos y plácidos, denunciando plenitud y paz.

Los pisos con sus líneas rectas perfectas en fuga, sugieren la profundidad en los espacios abiertos.

Su gama cromática es apastelada; trabaja el óleo en capas superpuestas logrando transparencias de una sensorialidad excepcional y una riqueza sobrecogedora.

Se declara Duprat adepto al “realismo simbólico”, pero mucho más importante que saber si puede inscribirse en algún movimiento contemporáneo, es descubrir la total originalidad que logra al ofrecer al espectador una cosmovisión plena de luz con imágenes humanas todo armonía y euritmia, que apuntan al rescate de la esperanza, en un mundo obsesionado por el consumismo, por los intereses materiales, despiadado e indiferente ante el espectáculo cotidiano de la violencia, de un enorme sector de la humanidad oprimida y desfallecientes por la hambruna y las guerras focalizadas que ofrecen una única salida: la muerte.

Las telas de Marcos Duprat desbordan luminosidad. Sus desnudos avanzan hacia un nuevo amanecer de la historia.

Afirma George Kubler en su libro: “La configuración del tiempo”, que: ”Todo artista importante revela una obsesión” y agrega que: “El más extraordinario innovador es funcionalmente un solitario”.

Marcos Duprat es ambas cosas confirmando así su condición de creador de primera magnitud en este último cuarto del siglo XX.

Prof. María Luisa Torrens

Directora del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo – Montevidéu, 1999

The recent developments in Marcos Duprat’s painting are centered in cenographic cuts of interiors, the living environment, penetrated by the symbolic narrative power of light.

The sun, erotic, energetic, comes form outside, trepasses the window, spreads its yellow pigmentation through the space and detaches itself from the structure, the floor, the objects and other formal components of those images. Ocasionally, a human presence is perceived in these settings.

The vigorous painting, of the works – now presently exposed ate the Renato Magalhães Gouvêa Escritório de Arte – grips the eye of the viewer. The thick pictorial surface reveals the artist’s search through decisive and determining brush strokes that reveal the creative tension and impetus in the making of these images.

It should be noticed that the paintings are composed by the fragments of the same, or of similar, interiors and also by some details, taken from the pictorial areas of those fragments.

These are all permeated by sunlight in different angles. These fragments are not repetitive. Each one of them registers partial views, certain pieces of furniture or details of the interior’s architecture. These fragments reveal segments of the artist’s eye as he looks at bits own living environment. This exploring eye investigates and reveals the diverse areas that compose the totality of the interiors, granting to light the role of a constant invader, and, “pour cause”, the leading element of those paintings.

Marcos Duprat’s exhibition deals specifically with paintings, its chromatic resources, and, naturally, its underlying design which sets parameters and borders for the composition of space.

In those paintings – in an apparently contradictory but vital juxtaposition – the constructivism of the interiors, the essential design of these images, and their architectural details or components confront and revitalize each other through the pictorial shower of warm, golden light which intermediates the relationship between the open cosmic universe outside and the closed, circumscribed and limited world of the interiors.

The creative act often surprises the artist. In this context, the act of creation is just a connection, a link in the duel between artistic thought and sensitiveness. In the creation and making of these works the power of light invades the constructivism of the composition and dissolves the precision of its drawing. The new artistic outcome of Marcos Duprat unfolds itself within this rather daring and beautiful parallel. The artist is a transgressor of this own expressive language in search of a wider scope and a greater depth.

Radha Abramo

Renato Magalhães Gouvêa Escritório de Arte – São Paulo, 1998

“For over two decades now, since the fatigue of abstractionism, the paradigm of Western painting has returned to the image. To the image that is violent or placid, impersonal or portrait-wise; hence the triumph of Bacon or Balthus, of the hyper-realists or of Lucien Freud. But, as wisely warned by those who first denounced the exhaustion of abstract art, the return to figuration can only be consistent if it builds upon a new rigour in technique and composition. In recent Brazilian art, none embodies such a rigour more thoroughly than Marcos Duprat.” – writes J .G. Merquior, Duprat’s domestic critic, in the catalogue of the painter’s 1990 exhibition in Milan. I believe this statement can be accepted as a starting point and a basic principle, in the process of understanding the Brazilian painter’s art on the occasion of his Hungarian exhibition. If one would surmise a slight contradiction between the clear objectivity of the sentence quoted and the notion of mystery, let me add immediately that it is, by far, not a contradiction. In fact, the multifaceted character of Duprat’s paintings is the result of the most divergent influences.

These sources range from the European classical tradition – through last century’s romanticism and its consequences in the twentieth century – to the latest tendencies, in which a pure and rational determining principle is the basis for the development of an enigmatic world concept. Concerning my former reference to romanticism, it was Delacroix who said, that in painting one could penetrate the mysteries of human passion only through learning and applying a sound and rigorous technique.

The mention of Vermeer as one of Duprat’s classic foregoers is not accidental. The analogy is quite right if one considers the Dutch master’s extraordinary intellectual clarity and austere humanism, his orderliness and meditative inclination, as well as his moving sensitivity towards the image, among the main features of his unsurpassably rich and exact technique. Criticisms of Duprat’s work searching out for further analogies, also mention Balthus subjects, except for its dark overtones, as the ones with more affinity to the nudes of the Brazilian painter. J.G. Merquior, quoted above, compares the atmosphere of Duprat’s representation with the “lyrical silence” of Morandi.

The Museum of Art of Sao Paulo held exhibitions of Duprat’s paintings in 1979 and 1988. In the former, the artist was introduced by two well-known critics, Vera Pedrosa and Carlos Rodriguez Saavedra. Both pointed out that, in the seventies, American hyperrealism, the immediate successor of pop-art, had a vigorous effect on the art of the Brazilian painter. That happened at a time when representation of the human figure followed new ways; the originality of Ouprat’s paintings stood out by means of an absolutely individual element: the joint interpretation of the figure and its own reflection. At that time, Saavedra wrote of him: “In Marcos Duprat’s painting representational values are meant to decode those which are non-representational. The visible foresees the invisible, the sensual discovers the spiritual. The painter’s language has mainly three signs: the organic, the abstract and the transparent. The first is the human figure, the second is the construction where man lives, and the third is light.” In 1990, the painter organized the elements of his art into a geometric scheme which can be interpreted as a constructive summary of his creator’s goal. The following elements exist in this scheme, which may be read both in its horizontal and vertical continuity: “interior, figure, still life; space, light, time; myth, reality, mystery”. The crystal-clear structure of spaces in his pictures (sometimes the only and independent subject of the painting is space itself) leads us to believe that classical constructivism has also been a major influence in Duprat’s art. Getting back to our starting point: Marcos Duprat, during his artistic education in Brazil, Japan and the United States, through deep studies of the old and contemporary masters, has acquired the necessary tools to create a new, -severe technique and composition, by means of which he embarked on a quest of new visual interrelations. Through the affectionate and sensitive illustration of the image, he has penetrated into the concealed world of human feelings. In spite of the often increasingly anarchistic character of today’s art manifestations, art history shows that true development has been always built on the common denominator of tradition and innovation: the elements discovered by earlier generations added to new ones. In Duprat’s paintings a matchless, unparalleled, individual world concept emerges in front of the spectator, the alloy of diverse influences.

This exhibition provides a selection of paintings and drawings of the last four years. Compared to his earlier work, there are signs of a certain change in these pictures, as if the artist is posing himself new questions. The leitmotiv of his art is still lyrical meditation: the refreshing and soothing silence that rules over the nudes in crystal-clear spaces, stiffened into momentary inertness, is also present in the still lives, which evoke the notion of timelessness, and in the harmonious interplay of light and reflection. His style has become, however, freer and more expressive, one might even say more realistic, and his brushwork has acquired a thicker, more perceptible quality. This change is especially prominent in his portraits, where one has the feeling that the tranquility of meditation has been jarred by an external, inconceivable emotion. The art of Marcos Duprat questions the past, the present and the future, on the thrilling edge between reality and mystery.

Géza Csorba

Deputy General Director – National Gallery of Hungary – Budapest, 1992

Explicitly linked to visible reality, to describable appearances, the paintings of Marcos Duprat, in all of those last years’ works, seem to constrain the viewer to a curious attitude of “mistrust” when in confrontation with those objects, places and figures presenting themselves in a fastly recognizable way, almost obvious in its directness and thematic clarity, and even in its depiction of the simplicity of daily life.

This becomes clear in every image, and even more so because each is a variation of the same subject, an objective exact “reference” being searched for the original motif of this whole sequence of pictures and, I suppose, for the final goal which it hopes to achieve in its transition from reality to fiction. Therefore the compositional rigor, the solidness of the bodies, the strong plastic sense, in short, the respect for the rules.

On the other hand, rendering enigmatic not only those objects but also their placement in space, in which they seem to be absorbed – leading us to believe that these are “happenings” captured in a second by the eye – there is very evidently an extraordinary lightness of treatment, an effusion of light that tends to shadow, partially disclose and finally disintegrate those objects and bodies, as if showing only their transparency. This is taken so far as to make the viewer suspect that those full. intense, male and female bodies, proudly placed in often misleading and complex architectures, multiplied within a rigorous sense of perspective, are nothing but a pretext to enhance their surrounding space and its leading role in these images.

In fact one ultimately finds out that without those figures, not at all strange to and never “stranged” because of their very belonging to and similitude to those spaces, the architecture would not be able to express the intentional ambiguity of those images.

It is for that very reason that Jacob Klintowitz in his essay, insisting on a “game of doubles”, on a “continuous confrontation of two parts”, has defined Duprat’s method as an “invention” of truth, which testifies for the creation of a “real” unreality, or, in other words, fiction. It is not by chance that Rodriguez Saavedra tries an even more subtle explanation: the representational values – to which Duprat does not resign in spite of running the risk of too literal a reading of his work – are tools for the decodification of the nonrepresentational values. Further more: “the visible foresees the invisible, the sensuous reveals the spiritual.”

In fact, the eventual borrowing of symbolist devices does not ever go beyond the domain of the figurative, of the visible appearances. On the whole, one seldom comes across the depiction of a “super-reality”, through distortion of the forms, “expressiveness” of the figures or a false perspective of the architecture. In what concerns the works’ titles, the concept of reflection results even more appropriate, as well as more coherent with the nature of the paintings, when it is not expressly brought up. In fact, the theme, with all its shades of ambiguity is also recognizable when the artist deals with figures in water, water and rocks, interiors with statues and columns, and eventually leads us to the metaphor of the interiors, of the objectiveness of visible elements, swiftly apprehended by the senses. And which, in its own turn, is misleading precisely because it is related to tangible matter.

Maybe Duprat’s true compositional “playing” is not that of setting “doubles” but reaching out to a sort of multiplicity which works out as a continuous exchange of the parts, in such a fast transformation that the eye perceives it as absolutely static. The sense of time – the perception of the concept of transition, openly stated in so many Passages, in indefinite ways inside-and-outside (or enclosure-and-opening), a concept reinforced by the hallucinating sequence of doors, windows and corridors, where a body, a statue or a still life are each nothing but another different “presence” – is finally enhanced through the handling of that effusion of light, which simultaneously reveals and hides. This sense of time is recognizable, in other cases, such as in those of the sets of repetitions of the same image with slight variations of color and placement, scanning the space through photograms, as parts of a puzzle, and also, in other images, through the fragmentation of the same object, sometimes in the horizontal sense (as in the case of the movement of clouds and waves), sometimes in a concentric sense, always simulating truth but projecting it beyond. As if each moment was nothing but a prefiguration of the next one.

If the earlier foundations of Duprat’s work, as pointed 0ut by P.M. Sardi, should be traced back to the “domineering current of hiper-realism” and the “influence of photography” in his formative years in New York, during the seventies, nowadays the direction towards which his figuration is taking, with an ever increasing drive, is that of a sort of new metaphysical language.

Roberto Sanesi

Centro Culturale San Fedele – Milano, 1990

For over two decades now, since the fatigue of abstractionism, the paradigm of western painting has returned to the image. To the image that is violent or placid, impersonal or portrait-wise: hence the triumph of Bacon or Balthus, of the hyper-realists or of Lucian Freud. But, as wisely warned by those who first denounced the exhaustion of abstract art, the return to figuration can only be consistent if it builds upon a new rigour in technique and composition. In recent Brazilian art, none embodies such a rigour more thoroughly than Marcos Duprat.

Quietly indifferent to the frenzy of the latest avant-gardes, Duprat has taken refuge in a strict faithfulness to what he himself calls “the enigma of visible reality”. It is a riddle that his oil paintings set, decipher and re-set by means of a luminous, crystal-clear style, with chromatic changes suggesting moments of magic transformations.

Planes are arranged, pigment layers overlap, colour emerges from “velatura” – a tecnique demanding a rhythm of execution miles away from the frentic legacy of Pollock and his ilk. It is a slow painting, adagio-like, favouring meditations on the double, the well pondered series, the research into depth – for such are the themes of his pictures, adept at focussing one image’s echo into another, reflections on mirrors and water, corridors unfolding into tunnels, delicate modulations of sequences.

When dealing with the human figure, especially the nude, Duprat conveys as much stillness as Balthus – except that his scenes are never a prelude to vice and malice. As he turns his attention to objects, the silence of his forms can be as lyrical as a Morandi. As for his landscapes – sky and sea under a Brazilian sun – they distill a glaucous harmony, bathing light, well-balanced masses. Invariably, perspective resolves itself into backgrounds of stylized geometry, fully structuring the felicitousness of representation.

Several predellas, diptychs and triptychs hint at a certain lust in trespassing limits, only to be soothed by a musical, suave, caressing space, underlining the cursive elegance of the lines. Light reverberates in the shadows: a little corner of the world quivers in the clear profile of an uncanny visuality; rooms, studies shine in a meridian and aethereal atmosphere, in a kind of Vermeerian mood; gravel and clouds appear to move forward and backwards; “ephebi” and “koires” – male and female figures – kneel or lie down, in deep introspection, looking at their own mirrors, real or imaginary.

This is pure poetry of the image; a very personal painting, where an extreme, wise austerity half conceals a constant dialogue with many a great figurative tradition. Marcos Duprat restores painting to the alluring domain of articulate representation, forever a source of dreams and reverie. The visible world becomes mysterious by dint of clarity and transparence. These images, so calm and translucent, seem to question both themselves and the onlooker. And what is a question, asks a master, but the desire of thought?

José Guilherme Merquior

MASP – São Paulo, 1988

If I extensively numbered the exhibitions I have presented until today, I would have an anthology of nearly all artistic movements in this century. Not only major artistic movements but also their variations: an impressive amount of forms of expression in the painting and sculpture areas. At this point, it would be relevant to remember that when I showed works by Carra and Soffici in my Milanese art gallery during the twenties, I had planned to include in the exhibition their futuristic works. The two masters did not agree, however, with the idea of showing their earlier works, mainly due to the fact that there was, at that moment, a revival of figurative painting in the Italian “Novecento” style. At that moment Giorgio Morandi was rated as the essential contemporary painter and my two guest artists did not care anymore for the experiments of Marinetti. Since then, first in my Milanese outpost, and later, after World War II, as director of the Museum of Art of Sao Paulo, I have promoted a long series of shows, from the metaphysical to the informal, from “concretismo” to surrealism, and I was able to follow all trends through the last decades, specially in Sao Paulo, where the diversity of artistic production has been assembling painters and sculptors among not only those who work on a more traditional direction but also those who pursue exclusively the “avant-garde”.

Recently, passing through Milan, I have had the opportunity of seeing the new paintings of the Brazilian artist Marcos Duprat. As I already knew, his work has remained figurative, a sort of painting which has recently attracted again the public’s attention and the critic’s discussions in relation to abstractionism.

In 1979, the Museum of Art of Sao Paulo dedicated an exhibition to Duprat. The artist was introduced then by critics Vera Pedrosa and Carlos Rodriguez Saadevra.

Vera has pointed out the roots of Duprat’s artistic background, in the seventies, in the United States, when the prevailing orientation was that of hyper-realism, as an immediate successor to the experiments of pop art.

At that moment there was an emphasis on photography and an interest in presenting the figure in a new way. Duprat’s originality was to work with the figure and its reflection on water and mirrors. Rodriguez Saavedra has written: “In Marcos Duprat’s painting, representational values are meant to decode those which are non representational. The visible foresees the invisible, the sensual discovers the spiritual. The painter’s language has mainly three signs: the organic, the abstract and the transparent. The first is the human figure, the second is the construction where man lives, and the third is light.” Both observations are correct. In the following years, the artist has pursued his call, giving evidence of a deeper and more intense concentration, as it is clearly indicated in his thoughtful and laboured drawings, previous studies for pictorial works. In these drawings, Duprat’s style … shows his sensitive perception of the reality of forms.

In my own times, I would qualify Duprat’s work quite simply as interesting, of natural and easy communication, if one takes into consideration that the artist wishes to be understood by the public aroused by his subject matter. Duprat is such an artist and what he has recently shown me in Milan confirms his intentions: to put on canvas his thoughts, permeated by his own poetic sense, in compositions in which nature has a substantial value. In some of those works, the artist paints landscapes and still lives formed by several squares, as in a “puzzle”, achieving an attractive and resourceful composition.

Having arrived at this point, I could only prolong myself in qualifying Duprat’s paintings and I would rather allow this to the visitors of the current show I have received in the Museum of Art of Sao Paulo.

Pietro Maria Bardi

MASP – São Paulo, 1988

It has been my privilege to have followed Marcos Duprat’s development in painting since he took it up as his chosen way of vital expression. That is, since he undertook it with the seriousness and dedication· of a professional artist.

Often I would go to Duprat’s studio to talk about his painting. Years have gone by since then and during this time I have not seen the evolution of his work. Now, as his second one-man exhibition in Washington D.C. approaches -this time at the Art Gallery of the Brazilian-American Cultural Institute- I see it through the distance of time, after a long absence.

His work has grown, has entered more definite channels. It has become freer, more sure of itself and has gained in depth. Marcos Duprat takes a deep dive in his work and surfaces again as a figure in one of his recent paintings. He brings back the assurance and the certainty one derives from the deep. He also comes up with new questions raised by the ripening of his experience and which are a prelude to new developments.

Throughout these years, Marcos Duprat has basically kept to the same subject matter. Nevertheless, his themes reemerge now with an enriched formal and chromatic structure -a change which can only be brought about by hard and concentrated work. The monologue sustained by his solitary figures facing the cosmos would inevitably demand the expansion of the physical space of the painting itself, and the canvases have consequently grown in dimension. The larger painting surface has created new problems which challenge the artist. The repeated duplication of the image and its reflection has called for the duplication of symmetries, now in the tangible dimension of diptychs.

These diptychs tend to transform the nature of borders, allowing for the possibility of a sequence in a physical and mental space. In this dialogue, one part is always the answer to the question introduced by the other: the divers submerge but they will return; the nudity that faces shadows is rewarded by light.

The variations on the theme of physical reality and its metamorphosis into the reality of the mirror image, embodied in Narcissus, are now taken up as notes of a melody that evolves on a staff provided by the whims of sea waves. These watery forms are in their turn firmly subjected to the artist’s own rigor and discipline. It is through this discipline that the artist sets the proportions of windows separating some of the reclining figures and the skies they contemplate. In this same way he creates the mirrored checkered floors where other figures move, the undulating underwater mosaics or yet the metaphysical frames of unexisting mirrors.

The artist works exclusively with oils, which gives his paintings a great variety of tones in the treatment of color and light, due to the benefits of slow drying. Marcos Duprat succeeds thus in setting his characters on a threshold, endowing them both with sensuality and modesty. Through the immateriality of earth, the clearness of water, the purity of atmosphere and the transparency of light, he offers them ideal conditions of expression in an unpolluted world, where life itself can breath and expand freely. This is the reason why his interiors have no ornaments and his figures are nudes. Figures, and not people, because they are not specifically anyone; because, in an abstract and general sense, they are everyone, the human being in search of identity and expression in a possible world.

Jose Neistein

BACI Art Gallery – Washington DC, 1980

EI arte de nuestro tiempo – en especial la poesía y la pintura – alimenta sus creaciones con lo imaginaria, lo real y lo subconsciente. (André Breton advirtió desde el primer momento la existencia de un punto en el que cesan las contradicciones establecidas por la razón formal, pero la pintura surrealista se empeñó en ilustrar esa doctrina, olvidando que, según el mismo Breton, una obra de tesis es como un regalo en el que se deja marcado el precio). Las obras de arte han sido siempre, por lo demás, la suma de los contrarios. Las paradojas integran en una expresión lógicamente aprehensible elementos aparentemente opuestos, extraños o dispares.

La obra de arte es, en ese sentido, una paradoja. EI artista ata en ella los cabos opuestos, revela el nexo invisible, la comunicación secreta. La obra de arte es un artificio que demuestra la verdad.

En la pintura de Marcos Duprat los elementos representativos sirven para cifrar -y descifrar- los elementos no representativos, los elementos visibles para adivinar los invisibles, los sensuales para descubrir los espirituales. EI idioma que inventa sólo tiene tres signos: uno orgánico, otro abstracto y un tercero traslúcido. EI primero es el cuerpo humano, el segundo la construcción en la que el hombre habita, el último es la luz. EI escenario en que se ubican estos signos es el aire, el mar, el espacio. La luz -signo transparente- integra y envuelve todos los otros.

Una obra con estas connotaciones parecería corresponder, dentro de una nomenclatura superficial, al género impresionista. Pero en el impresionismo esos elementos -cuerpo, paisaje, luz- son ubícuos, concretísimos, reconocibles y, sobre todo, agotan su ser en su apariencia. En la pintura de Marcos Duprat, en cambio, el mar es ideal; la construcción geométrica, vale decir abstracta; el hombre impersonal, de rostro indefinible. La irrealidad y la sensualidad deliberadas y contradictorias de esta pintura convergen y se resuelven en la sugestión de una imagen metafísica.

EI humano puro, el desnudo, contempla el mundo. En la quietud y en el silencio, en su soledad, el hombre se ha detenido frente al escenario deslumbrador: inmóvil, vuelto en reflexión a si mismo, está ensimismado.

Estas telas, en las que el virtuosismo del artista construye con tonos cálidos y tonos fríos una visión intelectual y resplandeciente del universo, responden a una antigua tradición filosófica y estética: la que hace de la meditación -o la melancolía- su símbolo más definido. Lo patentizan Narciso, un célebre grabado de Durero, el espejo de un autorretrato manierista. EI despojamiento ornamental y la sobriedad del gesto hacen frente aquí a la transparente belleza del mundo. Este devuelve al absorto la imagen exacta de su propio vacío. El mundo -lo prueban estas pinturas- es un reflejo de si mismo.

Carlos Rodriguez Saavedra

Lima – Peru, 1979

Nos idos de 1946, em crônica publicada na coluna As I Please do “Tribute” de Londres, George Owell escreveu (cito de memória) que a literatura absorvida na infância – e sobretudo a literatura barata – cria em nossa mente uma espécie de falso mapa do mundo, ao qual nos é dado de vez em quando recolher-nos, cartografia que, em alguns casos, se sobrepõe à realidade supostamente representada.

Trinta e poucos anos depois, a realidade parece estar cada vez mais confundida com as falsas cartografias. Para a geração que atualmente chega à maturidade – aquela a que pertence Marcos Duprat – não foi a literatura barata o que contribuiu de modo predominante para a formação de mundos ilusórios, mas (ao menos para as pessoas pertencentes a determinadas camadas sociais da civilização ocidental) foram as fontes visuais que passaram, de forma bastante rígida, a mapeá-los: o cinema, o vídeo, as suntuosas reproduções fotográficas das revistas e livros dedicados às artes, ao espetáculo, à publicidade, ao erotismo, à moda.

Num ambiente cultural dominado pela imagem – Susan Sontag discorre livremente sobre o assunto em “On Photography” – o tema do narcisismo é onipresente. É, no trabalho atual de Marcos Duprat, uma fonte recorrente de meditação. Tal imagem – a figura refletida num espelho que subitamente se parte ou no qual, de repente, aparece outro vulto – resulta de experiência vivida, foi urdida em devaneio brotou de sonho ou constitui imagem recolhida em um álbum, sequência de filme famoso? Se as figuras que ilustram os belos livros não exibem sinais de desgaste, que significa a fadiga em um olhar? Que é mais real, o reflexo ou o refletido? A que lado do espelho pertence Narciso? Existe, além de sua tênue representação, além da aparência, alguma realidade? Essas são algumas das indagações presentes na pintura de Marcos Duprat.

O artista passou a dedicar-se seriamente à pintura na década de 70. Seu acervo visual enriqueceu-se através da grande quantidade de informações recolhida durante a permanência – de anos – nos Estados Unidos. Estava então em indiscutível voga, naquele país, a fase hiper-realista que sucedeu às experiências “Pop” da década anterior. Duprat foi, portanto, exposto, em seus anos de formação, àquela tendência plástica que, na maior parte dos casos, parece haver se limitado a optar por passar uma mão de tinta sobre a reprodução fotográfica, como se, com isso, estivesse aproximando a pintura da “realidade”. O resultado dessa opção era, quase sempre, rígido e inanimado. A pintura hiper-realista, por outro lado, e salvo as honrosas exceções de sempre, tendia mais a glorificar que a criticar a civilização que a condicionava. Submeteu-se sem indagações à tirania da imagem fotográfica. Era uma pintura de aparente constatação. Como se nada existisse além dos instantes nela congelados, como se a incapacidade da reprodução fotográfica de vibrar além do instante correspondesse a uma suposta eliminação do tempo.

Embora às vezes partindo dos estímulos fotográficos dominantes do ambiente cultural em que se formava, Duprat preferiu, desde o início do seu aprendizado, elaborar um estilo sensível. Em seu trabalho, jamais esteve ausente a preocupação com a realidade e com o tempo. A pintura de seus primeiros anos é de anotações leves. A paleta é fresca e ao mesmo tempo sensual, produzindo uma agradável captação de impressões cromáticas e sentimentais.

Na fase atual, Marcos Duprat está empreendendo uma pintura de indagação. A paleta transformou-se intimista. Suas telas são estáticas, mas sem rigidez. O artista busca, sob diversos pontos de vista, explorar o tema do reflexo. É como se desejasse ultrapassar os limites da imagem, liberar-se das aparências que o prendem às falsas geografias; deter a espiral descendente que leva à absorção do ser pelo reflexo: Narciso. Suas figuras são quase sempre indefinidas, isoladas entre paredes que parecem de aço ou de vidro, retidas ante espelhos de metal ou de água. Consideram sua própria imagem, refletida em águas rasas, ou, às vezes, estão, nelas, semi-imersas. Destituídas de ornamentos, mas também aparentemente intocadas por quaisquer vicissitudes, ora parecem perdidas em devaneios, ora sugerem a entrega a uma auto-absorção sensual. Mas, em alguns dos quadros mais significativos desta exposição, encontram-se em atitude de expectativa. Estão em um limiar, talvez hesitantes diante da passagem. As portas e as janelas estão abertas, e, do outro lado, jorra a luz.

Vera Pedrosa

São Paulo, 1979

Published Reviews

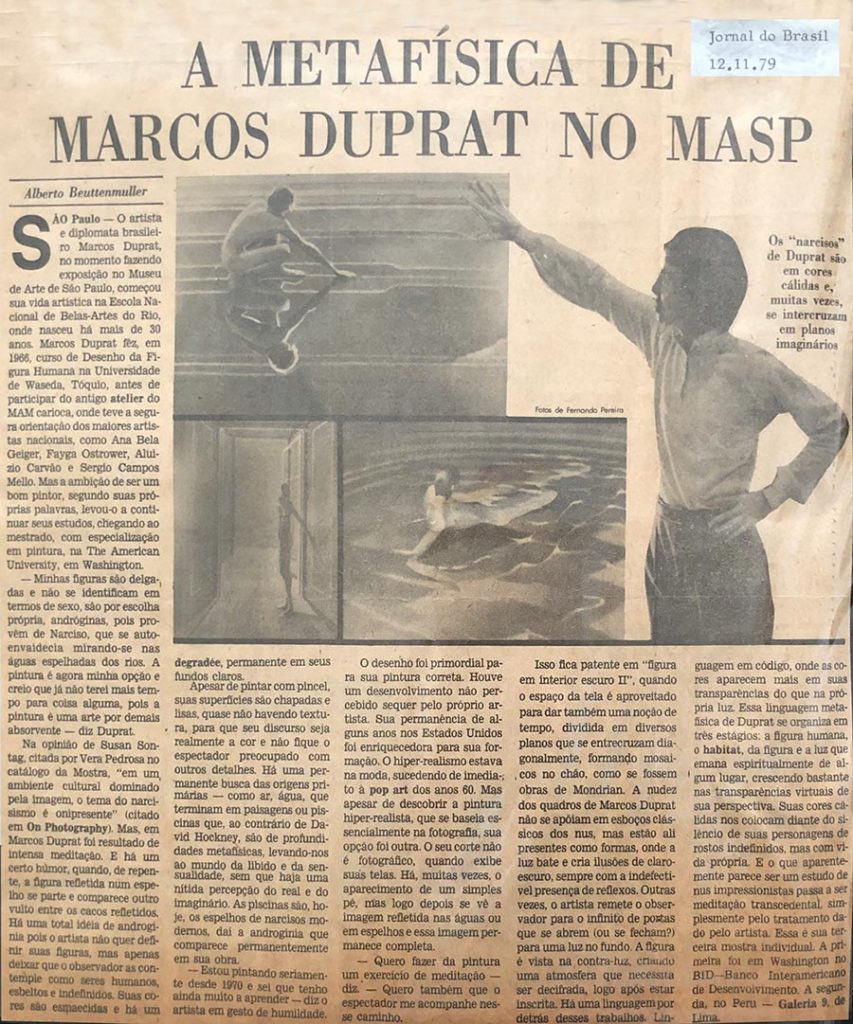

Jornal do Brasil – 1979

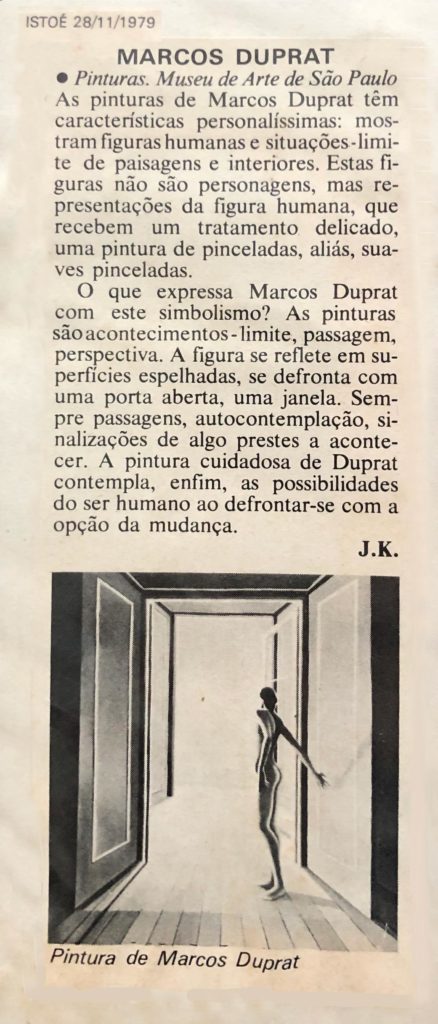

Isto É – 1979

Estado de São Paulo – 1979

Folha de São Paulo – 1979

Carlos Savedra – 1981

O Globo – 1982

Folha de São Paulo – 1985

Jornal do Brasil – 1985

Estado de São Paulo – 1985

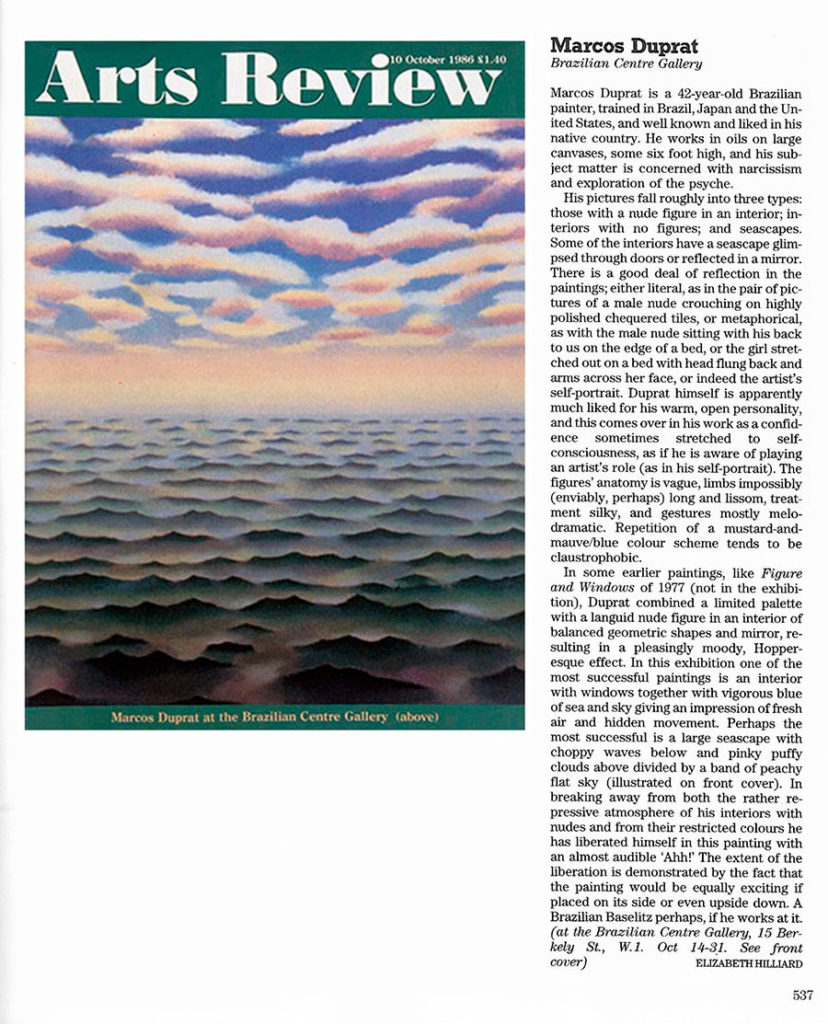

Arts Review – 1986

Arts Review – 1986

O Globo – 1988

Corriere Della Sera – 1990

Jornal do Brasil – 1996

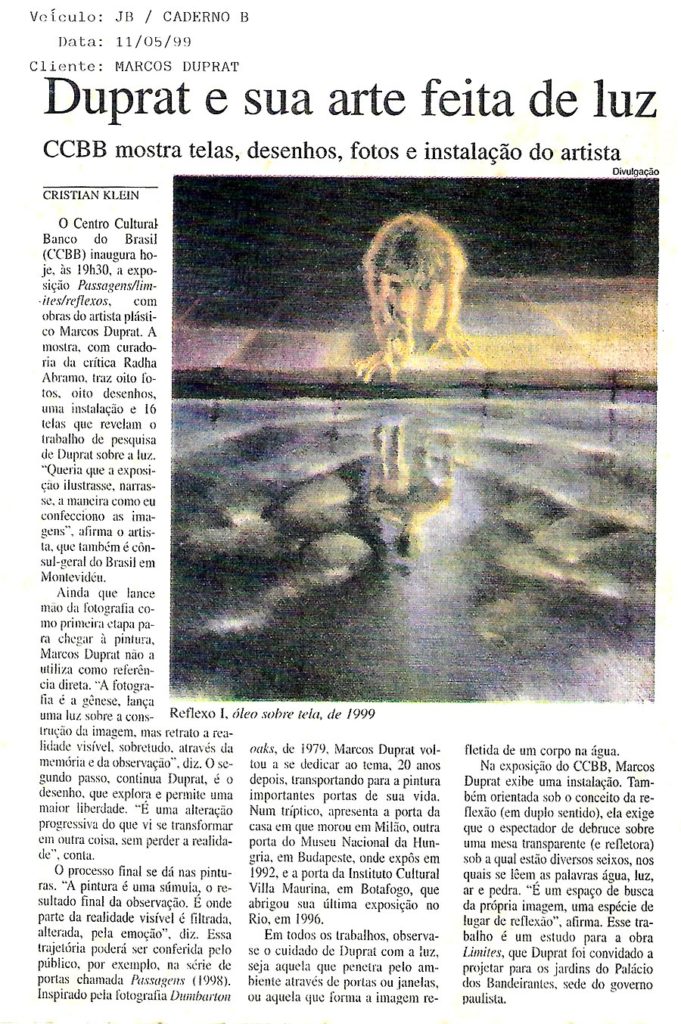

Jornal do Brasil – 1999

Jornal do Brasil – 1999

Jornal do Brasil – 1999

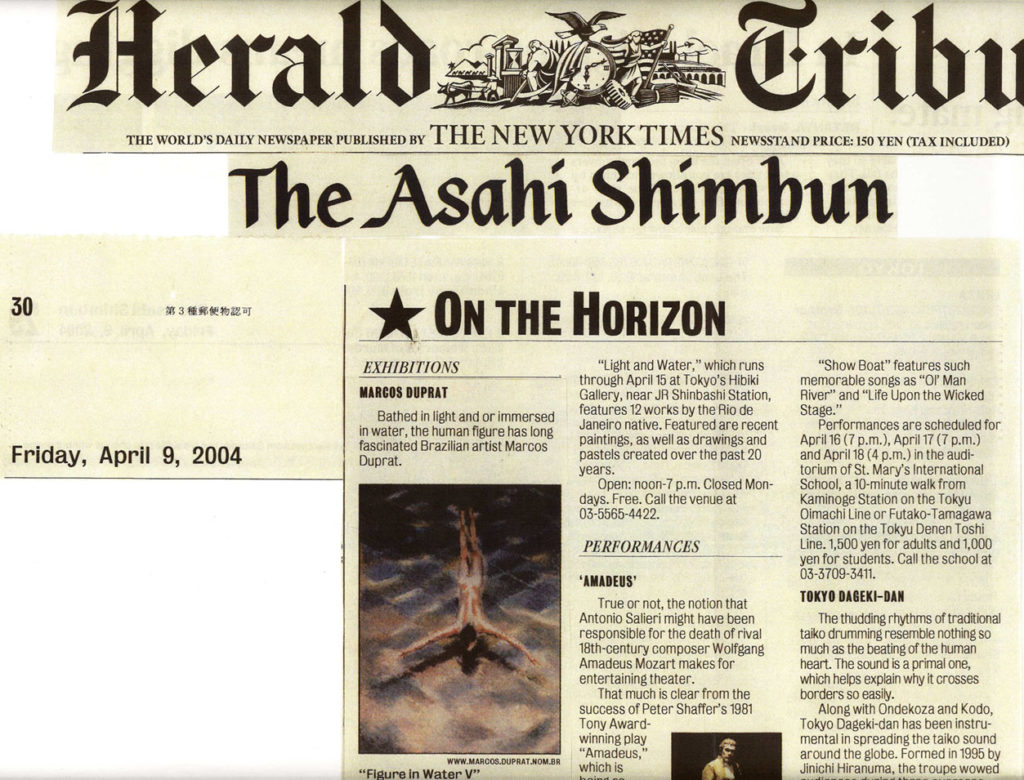

Asahi Shinbum – 2004

The Daily Yomiuri – 2004

Harald Tribune – 2004

Metropolis Japan – 2004

The Japan Times – 2004

O Globo – 2008

O Globo – 2008